Prisoners of war in World War II

© Lesya Kharchenko

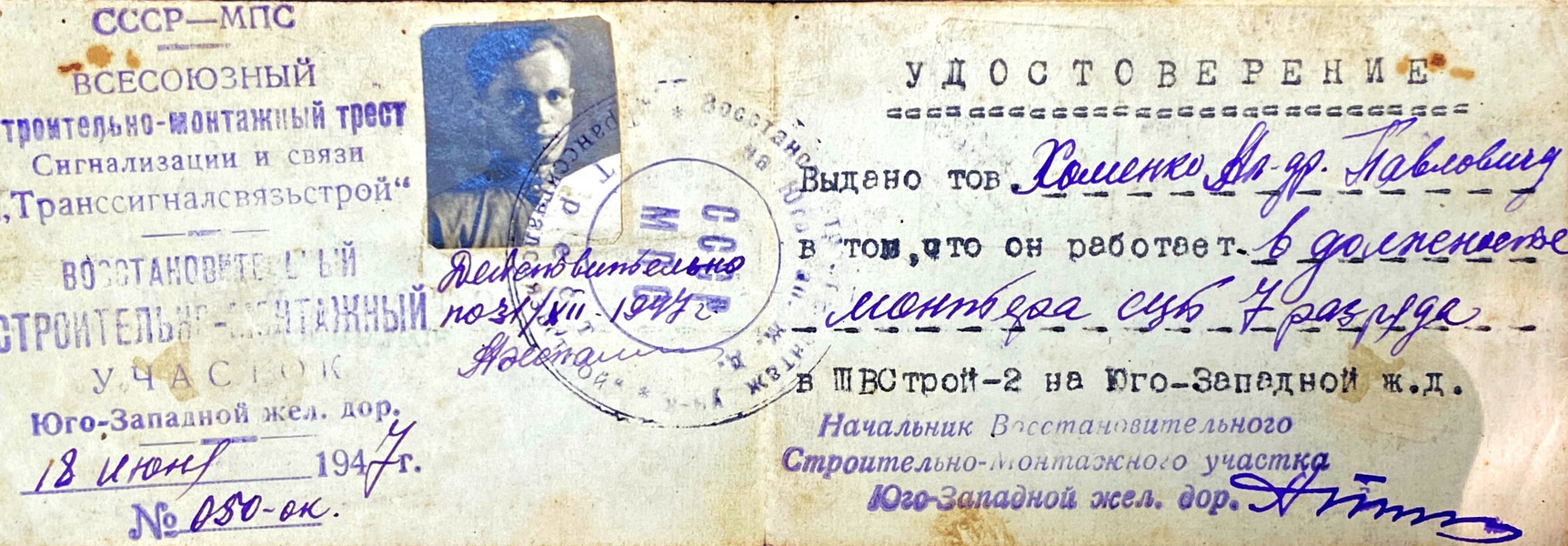

According to the organization Kontakty which is concerned with the victims of National Socialism, only 15 prisoners of war of World War II are still alive in Ukraine. Most of them have no mobility or only limited mobility and need help to cope with everyday life. How do they feel about the current Russian war of aggression against Ukraine? On behalf of the EVZ Foundation, the journalist Lesya Kharchenko met with Oleksandr Pavlovych Khomenko, a former prisoner of war.

Oleksandr Pavlovych Khomenko

© Lesya Kharchenko

Oleksandr Pavlovych Khomenko was born in November 1923 in the village of Davydky in the Zhytomyr region, Ukraine. He studied at the Technical College of Railway Studies in Kyiv. In 1942, he was called up to the front and served as a reconnaissance officer in an artillery regiment. He was wounded near Kharkiv and taken prisoner; he remained there for three years.

After the war, Oleksandr Pavlovych obtained two university degrees: He studied physics and mathematics at the Pedagogical Institute in Kyiv and graduated from the Kyiv Polytechnic Institute. He worked as a teacher until he retired.

A Cautious Approach

"Oleksandr Pavlovych!", I shout at the wooden gate, which is locked by a bolt from the inside. "Oleksandr Pavlovych!" - silence. Across the street, a young man sits on the porch of a house reading a newspaper; he appears oblivious to my shouts. A neighbor who is doing some weeding stops for a moment. I ask her: "Do you know if Oleksandr Pavlovych is home?" She turns to me, wiping her hands on her apron: "He should be home. Unless something has happened. After all, the two of them are no spring chickens." She leaves her work and walks over to me. We are calling out together already – but no one answers.

The neighbor is concerned: "I haven't seen them for two days now. But the greenhouse is open; maybe his wife, Mariya Markovna, works in there. And Oleksandr Pavlovych doesn't hear us."

We call again, pressing the bell we find on a small shed next to the gate. After a few minutes, something slowly stirs on the porch. "Well, thank God, you're still alive," says the neighbor. "I'll leave you two to it then."

Oleksandr Pavlovych is a tall, slim man, but he moves slowly - his legs are heavy. He gives a friendly greeting: "Come in, I'm making breakfast for me and my wife, she's sick." Mariya Markovna, Oleksandr Pavlovych's wife, is actually lying in the room and is unable to get up. She was born in 1930. Oleksandr Pavlovych looks after her. Her daughter who has also already retired lives nearby. Her granddaughter fled to Spain with her son when Russia invaded Ukraine. "But she is our only support," Oleksandr Pavlovych complains. We sit down on the steps of the porch.

Can you tell me how you were imprisoned?

O. P.: In 1942, when I was 19, I was conscripted into the army. The fighting took place near Kharkiv, in Izyum where fighting against the Russians is also happening right now. When the Germans broke through the front, we were surrounded and began retreating toward Stalingrad. That is where I was wounded.

Look (he shows me his collarbone and back underneath his shirt) at the hole I have here. That's where the bullet exited. I used to pull my zipper all the way up; the bullet hit right there. It took out a piece of my body, and come out between my shoulders. My spine was exposed, a huge bleeding wound. But without the zip, I would have been killed outright. There were no blood transfusions available because the army was in retreat. Whilst they were putting a bandage on me, I heard the words: "He's not going to survive". But I was conscious and I answered: No, I'm going to survive. Apparently, the bandage was put well. It was very hard for a few days; I kept losing consciousness, then it stopped and things started to get better. Everyone was surprised I survived. And now I am 99 years old. See!

I was imprisoned with this injury. I was transported from one camp to the next group of other wounded people. I remember Kantemirovka, Kremenchuk. I was there for nearly a year. The treatment was primitive, I was taken care of by my fellow prisoners; there were no procedures, everything was just treated with bandages. The main drug was Rivanol (an antiseptic); there were no other drugs. Only those who had a strong, healthy constitution survived. The fact that prisoners have died by the dozen is nothing new. Firstly, due to injuries. Secondly, people were just not psychologically able to endure the conditions. This often resulted in the most unexpected incidents. People despaired of everything. But I lived with a conviction that I would live to see peace. I felt sure that Hitler could not win.

Already in the fall of 1942 I was sent to the prisoner-of-war camp Stalag VII-A in Germany with a group of more than 1,000 other prisoners. That was in Bavaria. The wound had mended and I was no longer wearing a bandage. I worked in the BMW factory close to the Dachau concentration camp. The factory manufactured aircraft. And the workshop where I ended up produced the aircraft engines. The crew which worked with me in the machine shop consisted of our blokes who had been taken prisoner at the beginning of the war.

How were you treated in Germany?

O. P.: I worked under the supervision of a German master; we made Junkers-87 and Junkers-88 and installed other equipment against radar interception.

One prisoner of war named Gavrilov, who was a specialist in metalwork and mechanical engineering, worked in the machine workshop. During one of the evening checks, it turned out that a worker from the workshop was missing. And it was Gavrilov. They sounded the alarm on the site, but the search was fruitless. Then, the foreman who worked with Gavrilov recalled that he was a very resourceful man. He decided to look in the basement of the machine shop that could be locked. He suspected Gavrilov might have made a copy of a key. And indeed, they opened the cellar and found him there. He was tortured and then shot.

The shooting of Gavrilov was a show execution – the command of the camp guards was held by a subordinate officer of the SS troops; it was an important location, an airport. The guards had the right to shoot anyone who fled or prepared to escape with impunity. However, if a fugitive ended up in another unit, the matter did not result in a firing squad. They were handed over to the central camp, where they were punished, fined, etc., but there was no question of shooting them.

Under these conditions, I decided to organize an escape and break out. It was very risky, really dangerous. We were kept under strict guard. Evidently, I was denounced to a secret group. I was summoned for interrogation and then isolated from the camp as a suspicious individual. A few months later I was sent to the town of Dingolfing an der Isar, to an agricultural machine factory. There I came into contact with a group of young men and we decided to escape again.

During the years of my imprisonment, I made four attempts to escape, all of which were unsuccessful. I was punished. The first escape was punished with seven days solitary confinement, the second with 20 days, then 28; and then I was sent to a punishment battalion. We were transferred to the security area of a unit which belonged to a different camp than the one we had escaped from. Escape is a very dangerous moment in the life of a prisoner of war.

What was the most difficult time?

O. P.: After my third escape, I got 28 days solitary confinement and then sent to Strafarbeitskommando (punishment battalion) 190 of Camp VII A, which was used in a quarry to the east of Ingolstadt on the left bank of the Danube. The team consisted of 20 to 25 people who lived there on a permanent basis. The hut was primitive and bordered from the rock by a wall. There was also a kitchen covered with a roof where Germans who weren't prisoners of war worked. The whole place was surrounded by barbed wire. We could only move from the barracks to the quarry and from the quarry to the barracks. I spent three months there. I didn't run away after that.

Yes, Camp 190 was a tough test, pure horror. People suffered injuries and lost their health there. There was a standard for a person: 18 carloads of stone per shift (one carload was one cubic meter). Failure to achieve this norm was punished by food deprivation or corporal punishment. It was the hardest time. In order not to have to comply with the required standard, I put my finger on a stone and hit it with a hammer, injuring myself intentionally. The Germans reacted suspiciously, but the standard changed. They put me to work on a conveyor belt. The carts went up over the belt, turned, and the stones fell into the transport carriage. I still have the scar. When it's cold, it starts to hurt.

It was different with the other types of work. It was the usual stuff: You do your job and that's that. A lot depended on contact with the masters who supervised the prisoners of war. For example, whether you could talk to the Germans. Sometimes they wondered where I got my language skills. But I did well in school. These language skills helped me a lot. The Germans looked at me differently.

What did the experience of imprisonment give you?

O. P.: That's a complicated question. For me, it was important to survive. The conditions under which the prisoners lived and worked were extremely harsh. In Germany, I was like someone who just had to work and wasn't even allowed to think about another life. You are just a prisoner of war and nothing else.

Hunger was the most significant issue for the prisoners of war. I had lost faith that I would ever eat a potato. And when I was released from captivity and was awaiting repatriation, it was like paradise.

But I always believed I would be free one day. The belief in freedom, I realized after everything, was the most important thing which guided me in my life.

Were you persecuted after the war as a former prisoner of war in the Soviet Union?

O. P.: The path of my life was very complicated. The status of a prisoner of war entailed certain restrictions. For example, I applied for a postgraduate program in mathematics at the Academy of Sciences, but I was rejected for precisely that reason. After Stalin's death the situation changed a little, but when it came to rewarding work successes, the restrictions were very clear. It's painful to remember, but that's the reality.

I was lucky because they were not especially interested in my CV for my job. But when I was invited to join the Communist Party, adversaries appeared who started digging into my biography. That is why I had to give up my job in the Zhytomyr region and move to the Kyiv region.

Facts and Figures About the Topic

- After the European Jews, the former Soviet prisoners of war represent the highest number of victims of World War II, with approximately 3.3 million deaths.

- According to the German Foundations Act, prisoners of war were excluded from payments to forced laborers. 20,000 applications from former Soviet prisoners of war from Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine were consequently not be recognized.

- In 2003, the Kontakty Association used donations to launch the "Citizens' Commitment to Forgotten Victims of National Socialism" project. In this way, former Soviet prisoners of war were able to receive very modest sums of money as a gesture of recognition. In total, 7,404 former Soviet prisoners of war in Armenia, Belarus, Estonia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Republic of Moldova, and Ukraine were reached and donations were provided amounting to EUR 4,339,108.14.

- In Ukraine, the association has helped a total of 2,250 former Soviet prisoners of war since 2003 with a total of EUR 872,000.

- In 2015, the German Federal Government provided approximately 1,000 former Soviet prisoners of war still alive with a recognition payment of EUR 2,500 each.

Oleksandr Pavlovych Khomenko

© Lesya Kharchenko

The War - Then and Now

Despite his considerable age, Oleksandr Pavlovych is mentally very clear; a few years ago he wrote a book about the historically complex relations as well as Russia's hostility towards Ukraine. War intrudes into our conversations all by itself. The former prisoner of war is very well acquainted with the latest types of weapons, and he follows events at the front. I ask him: "Where do you get your information?"-"I read the newspaper Ukraina Moloda and analyze a lot of things." The siren sounds twice during the conversation - the air-raid alarm. But Oleksandr Pavlovych pays no attention to it – maybe he doesn't hear it.

Eighty years have passed since your imprisonment, and now there's a war again. Did you expect that?

O. P.: I knew about the history of Ukraine and I was convinced that nothing good could be expected from Russia. I was born in 1923 and grew up in the countryside of Polesia, in the village of Davydky in the Zhytomyr region. Based on everything reported in the press, I assumed the Russians would advance through the Narodychi district – and that's what happened. They passed through this area, leaving devastation in their wake. They also use rockets to destroy the village where I was born. The same thing happened to neighboring villages. They blew up the bridges when they were forced to retreat. I heard that a rocket hit the cemetery. That's where my parents are buried. I can't get there to look at it. I feel hatred towards my enemies – such things are strange and incomprehensible to me. You see what kind of war this is.

And what would you say to today's prisoners of war?

O. P.: It is hard for me to say anything to them. I marvel at them and I suffer with them, they endure things that our prisoners of war in Germany didn't have to go through during World War II. I mean in particular this kind of torture that happens in Russia, that really is a barbaric practice. The situation is extremely difficult.

I would like to tell our men to have faith in their country despite everything. The complexity of the circumstances in which Ukraine finds itself is something we have never seen before in history. I have the impression that the life of Ukrainians has reached the most extreme level of difficulty. How it will continue is hard for me to imagine. But I was always convinced that Ukraine will be a strong state with an own future.

_______________________________________________

I spent several hours talking to Oleksandr Pavlovych. Despite the long, tiring conversation, he didn't appear to want to let go of his interlocutor he encountered by chance. Being a prisoner of war was only a part of his memories.

He readily shared how he was able to establish his life in the civilian setting after World War II. Telling about his many years of work at the school where he taught physics, mathematics, and German. Recently, he had a visit from his school students, a group he had taught as a classroom teacher. They were celebrating their 50th high school graduation and they decided to visit their teacher. A whole delegation came; the school students themselves were now pensioners already. "Isn't this a blessing?" asks the 98-year-old former prisoner of war.

He accompanies me to the gate, watching me until I turn the corner. He's wearing a white T-shirt, and as he turns to walk to his hut, the shirt has the words: "I love Kryukivshchyna." Kryukivshchyna is the village near Kyiv where he lives with his wife and which he will never leave.

The interview took place in late summer 2022.