Lost letters

© Lesya Kharchenko

The discovery of numerous letters from forced laborers in Ukrainian archives started with a family story and a secret. The three Strojewa sisters were deported to Germany in 1943 from a simple village hut in Kalynivka in the Makariv district, close to Kiev, to carry out forced labor in a rolling stock manufacturer in Gotha, Thuringia.

The historian and his family history

The discovery of numerous letters from forced laborers in Ukrainian archives started with a family story and a secret. The three Strojewa sisters were deported to Germany in 1943 from a simple village hut in Kalynivka in the Makariv district, close to Kiev, to carry out forced labor in a rolling stock manufacturer in Gotha, Thuringia.

Nonna, the eldest of the three sisters born in 1922, returned home after the war but didn't even survive six months after contracting tuberculosis in Germany. Tamara, the middle sister, 1925, never returned from Germany; what happened to her was unknown. And Josephina, born in 1927, lived into the 2000s - but she never talked about forced labor or her missing sister Tamara. But without her great-nephew Witali, no one would have known about the fate of one of the sisters.

Witali Geds, a historian and specialist on World War II, was told by his grandmother after defending his dissertation on the occupation of Kiev: "You're the expert, why don't you ask around and see if you can find out anything about my sisters?" And so he began to search. In a monograph he read that letters from "Eastern workers" were stored in the archives of the Kiev administrative region.

"I still remember to this day: Inventory item 4826, description 1, file 286. And the very first bundle of letters came from my home village of Kalynivka in the Makariv district. And the first letter at the top of the pile was a letter from my grandmother Tamara, who never returned from Germany, with a picture of the three sisters at work," Witali recalls. "In the letter, Tamara said that she was in a relationship with a Frenchman, and that she wanted to get married and go to France."

In this way, the family learned for the first time that their sister Tamara had not died in the course of forced labor and that they might have relatives living somewhere in France.

There, in the archives, Witali also found the so-called "filtration file" of one of the other sisters, Josephine, and now understood why she never wanted to talk about her years in Germany. Until Stalin's death in 1953, she was summoned for interrogation every six months and asked about her sisters.

Witali brought his mother a copy of Tamara's letter. Her reaction was unusually fierce: She cried looking at the pictures of her aunts, two of which she had never seen, overwhelmed with memories. When she learned that there were ten more letters from her village in the archives, she said: "I got this letter, why shouldn't others get their letters as well?" And so Witali began to deliver the letters in his village. Letters from "Eastern workers" that had been sitting in the archives for more than seventy years.

"Eastern workers"

The "use of foreigners" by the National Socialists between 1939-1945 was the biggest mass use of foreigners in the economy of a single country since the days of slavery.

In the course of the World War II, some 13.5 million people from 26 European countries worked on the territory of National Socialist Germany, its allies and in countries occupied by Germany. Of these, 4.5 million were prisoners of war and 8.5 million were civilian workers and concentration camp prisoners.

The largest group of forced laborers consisted of residents of the occupied territories of the USSR, called "Eastern workers". Most of them were deported from what is now Ukraine to the Reich between 1942 and 1944, using brute force.

Most of the "Eastern workers" were very young: They were on average between 20 and 24 years old; a third of them had not yet reached the age of thirty. There are quite a few reports of children as young as 13-14 years old being classified as "able to work" in the labor force lists.

"They were treated like slaves and worse," said historian Tatjana Pastushenko. "Poor living conditions, inadequate food, hard work, disastrous hygienic and sanitary conditions in camps resulted in the highest number of injuries and deaths among 'Eastern workers' as compared to workers from other countries. Women were often sexually abused."

Workers' chances of survival depended on where they were employed: in state production, where working conditions were the harshest, or with a farmer, where it was easier to survive.

After hostilities in Europe ended, most forced laborers from the East were stranded in camps for displaced persons. Instead of receiving medical care and material aid, millions of people were forced to undergo political filtration by the NKVD, NKGB, and SMERSH counterintelligence services. After this review, only 58% of those who returned went back to their families. 19% were immediately drafted into the Red Army, 14% were placed in so-called "labor battalions," and 6.5% were arrested by NKVD units as enemies of the people.

In 1946, the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg declared the National Socialist practice of forced labor of foreigners to be a crime against humanity.

But as long as the Soviet Union existed, the so-called "Eastern workers" were considered to be "unreliable." That is the reason why many of them did not talk about their past. The situation didn't change radically until the end of the 1980s when the first articles about former "Eastern workers" and concentration camp prisoners appeared in the press. The German government's humanitarian payments to former "Eastern workers" and the associated public discourse in Ukrainian society contributed significantly to accelerating this process.

How did the letters get into the archives?

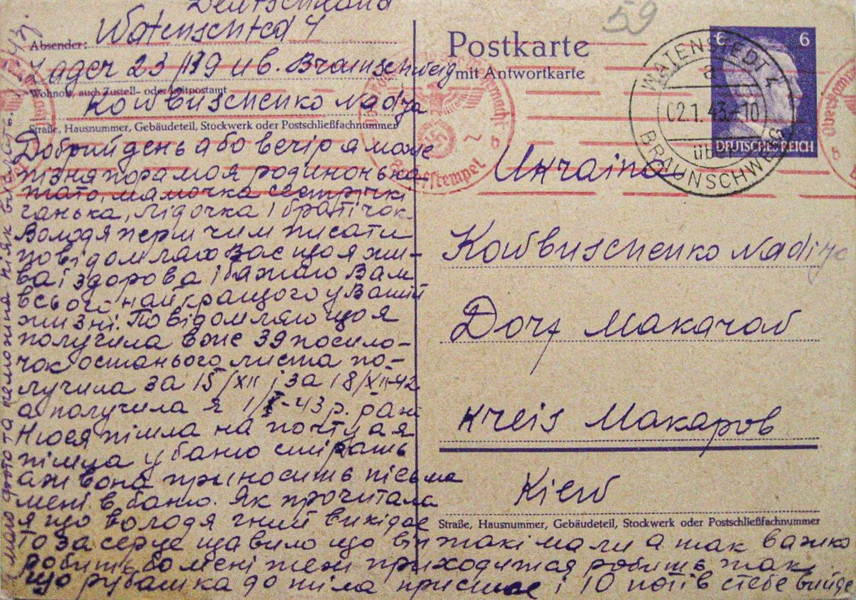

In November 1943, Soviet troops liberated Kiev, and the NKVD immediately had all letters from Germany confiscated from post offices. All letters that came from Germany were "adorned" with the National Socialist coat of arms or with a portrait of Hitler. As the bold blackened sections or the stamps with the letters "Ab" show, these letters were controlled by the National Socialist censors.

Instructions were not to deliver them to the relatives. At the end of the war, the NKVD ordered these letters to be transferred in sacks to the Kiev archives for secret storage, to be burned over time.

The "secret" marking was removed from the letters after perestroika. In 2018, the 75-year secrecy ended and Witali Geds and other historical researchers had the opportunity to copy the letters and to pass them on to the addressees or their descendants.

Of 50,000 undelivered letters from forced laborers in the Kiev archives, Witali has now been able to deliver about 3,000. He is assisted by village leaders, priests, librarians, teachers and volunteers who search for relatives of the letter writers.

Postman of history

In December 2021, Witali climbed into his old Kia and drove to the neighboring village of Nebelyzja. At the gate of her house, Lesya Kulinska, who is waiting for her letter, already meets him with excitement.

"Once I was with Witali on a trip to Lviv and I showed him a picture of my mother that I carry in my wallet. Later he sent a list of letters for our village," Lesya reports. "I looked and there was my grandfather's last name, there was a letter for him from my mother Katerina Fedorenko. I was shocked: How could that be? Especially since all those people were no longer alive."

Lesya looked at the short letter, read it, invited Witali into the house and began to remember, showing him pictures and telling stories. She will now keep the letter as an heirloom for her grandchildren.

For Witali, the most beautiful moments are the encounters with relatives who are eagerly awaiting a letter and looking forward to it. Of the 3,000 letters he had already been able to deliver, five letters went to people who had written the letters themselves.

"I still feel moved when I think back to a meeting in the town of Yahotyn where I delivered a letter to centenarian Maria Garkawenko on her birthday. The whole family had gathered; they knew we were coming. 'Then read the letter to us'. So I start to read, the woman interrupts me and quotes the letter she wrote 77 years ago, word for word. Her son said she didn't remember what she had done the day before, and yet she remembered that letter, word for word."

One day, Witali discovered 25 letters from one person: Nadja Kowbuschtschenko. That's a lot because forced laborers in Nazi Germany were only allowed to write a letter every two weeks on average.

The undelivered letters even led to a family squabble, as it turned out. After the war, brother and sister fell out so badly that they did not speak to each other for some years. The brother accused Nadja of not writing and not being interested in the fate of the family. Nadja maintained that she had written. Unfortunately, the proof came too late, at a time when neither brother nor sister was still alive.

The archives today

In the meantime, Witali has contacted all the regional archives in Ukraine and discovered that thousands of such letters are also stored there - roughly estimated at 200,000 in total. They have not yet been fully researched or systematized.

In some Ukrainian archives, in addition to letters from forced laborers, there are also letters from German soldiers which the Nazi troops were not able to destroy in time during their retreat. These are also letters that were left on the road and never reached their addressees.

In the meantime, other historians are also participating in this work; they want to ensure that all letters reach their addressees. Or at least their children and grandchildren. In addition, Witali and his colleagues dream of building an electronic database of forced laborers where all information from the archives with photos, letters and filtration files are to be stored.

"When you look into the eyes of people who have received letters from the past," says Witali Geds, "you understand that there are people for whom this work is very important. And as long as that work is needed, we'll keep on doing it."