80th Anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising: Exhibition at POLIN Museum

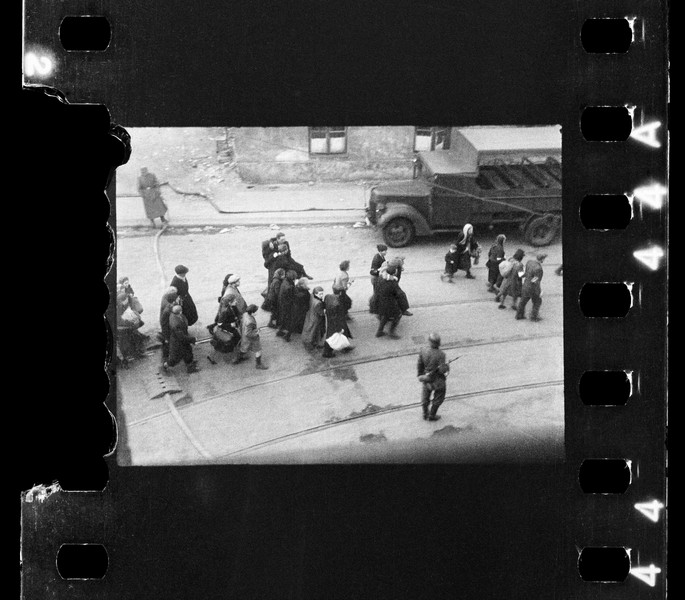

© Z. L. Grzywaczewski

How did the Jewish civilian population in the ghetto fare during this time? They hid in bunkers during the uprising, resisting the calls for deportation that would lead to death. Their silent act of resistance was as important as the armed struggle.

The Warsaw Museum POLIN (Museum of the History of Polish Jews) tells the story in the special exhibition "Around Us a Sea of Fire. The Fate of Jewish Civilians During the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising" their stories.

The exhibition makers:focused on records from diaries written during the uprising. These words are often all that survived, the only trace left of the people.

The project is funded by the Claims Conference, the German Federal Ministry of Finance (BMF) and the EVZ Foundation as part of the Holocaust Education funding program.

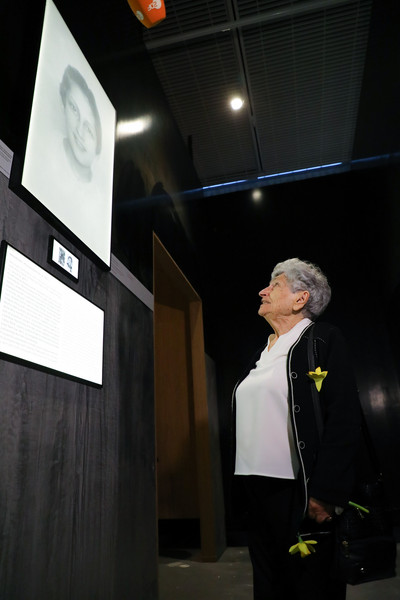

Zuzanna Schnepf-Kołacz

© Maciek Jaźwiecki

3 Questions for Zuzanna Schnepf-Kołacz

Curator of the exhibition "Around Us a Sea of Fire. The fate of the Jewish civilian population during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising" at the POLIN Museum.

What kind of stories does the exhibition you curated on the occasion of the 80th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising wants to tell? What perspectives are you focusing on?

The exhibition "Around us a sea of fire” tells the story of civilian Jews imprisoned in the ghetto during the Uprising. This story was for many years overshadowed by the narration about armed uprising. It hasn’t been presented to a wider public. Almost 50 000 people were hiding in the underground bunkers or other hideouts. In case of most of them we don’t know even their names. They didn’t have much hope to rescue but they wanted to oppose the Nazis. They refuse to follow the German orders to assemble at collection points, they stayed in hiding. They fought the despair, loneliness, starvation, and fear, each and every "day, hour, minute." Their silent resistance was as important as armed combat.

We tell the story of civilians with their own words, using their testimonies written during the war or immediately after. It is often the only historical material that document their fate and that remained until today. We present the civilian story from the perspective of the victims – Jews. Therefore we decided not to use Nazi documents and visual materials as we don’t want to look on Jews through German propaganda materials, created by the perpetrators.

This exhibition is not a historical presentation of the subject in a traditional understanding. There are very limited museum commentaries which present events form a wider historical point of view. The main material upon which we construct the narration are excerpts of personal accounts. Many of them describes feelings, thoughts and experiences of their authors. It is a very personal perspective, close to people and their emotions.

Since almost all objects and keepsakes from the Warsaw Ghetto were destroyed and burned, the exhibition is based on testimonies: How did you manage to make the experiences and feelings of the authors visible in an exhibition?

We treat words from the testimonies of Jewish civilians as very precious artefacts of the exhibition. Our aim was to give to these words a kind of material form, and to create the design of exhibition upon them. We invited Małgorzata Szczęśniak, a leading Polish scenographer and recipient of the 2021 International Opera Award to create the scenography of the exhibition. Taking the perspective of civilians, the exhibition presents key events of the uprising, places of torment, and hiding places. The scenography evokes the reality of confinement: the darkness, the lack of space and air. At the same time the space designed by Małgorzata Szczęśniak and Saskia Hellmann reflects in a metaphorical way feelings and emotions of people imprisoned in the ghetto, hidden underground.

Musical soundscape designed especially for this exhibition by Paweł Mykietyn is another important dimension of the display. It is a key component of the visitor experience which includes passages from diaries and sounds inspired by those described in the testimonies as the only sign of what was happening above ground.

How long did you and your team work on the curation of the exhibition? What were the biggest challenges in curating?

We’ve begun working on the exhibition almost two years ago. Our starting point was the concept to tell the story of Jewish civilians in the ghetto during the Uprising from their own perspective. Our main material were their testimonies. The biggest challenge was how to present this content in terms of exhibition’s visual language and design. For this reason the scenography and soundscape inspired by the personal accounts are the key elements of the exhibit.

The lack of visual materials and artefacts was another difficulty. In case of some of our heroes we had only a few pages of his or her testimony and nothing more. Our curatorial workshop involved not only in depth historical research but also searching and contacting families of the heroes whose stories are presented on the exhibition. We managed to obtain photos and documents from their family collections.

The same way, by searching and contacting descendants, we gain two very unique series of photographs taken by Poles inside and outside the ghetto during the Uprising. They have never been presented before in public. first material consists in photographic film which contains a set of photos taken during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising by Zbigniew Leszek Grzywaczewski, a firefighter at the Warsaw Fire Brigade. The photos are priceless. These are the only photos that we know of taken inside the ghetto during the Uprising whose authors are not the German perpetrators. Several decades after the war, Maciej Grzywaczewski, Zbigniew Leszek’s son, found the negatives. He was looking for them for over half a year, upon our request.

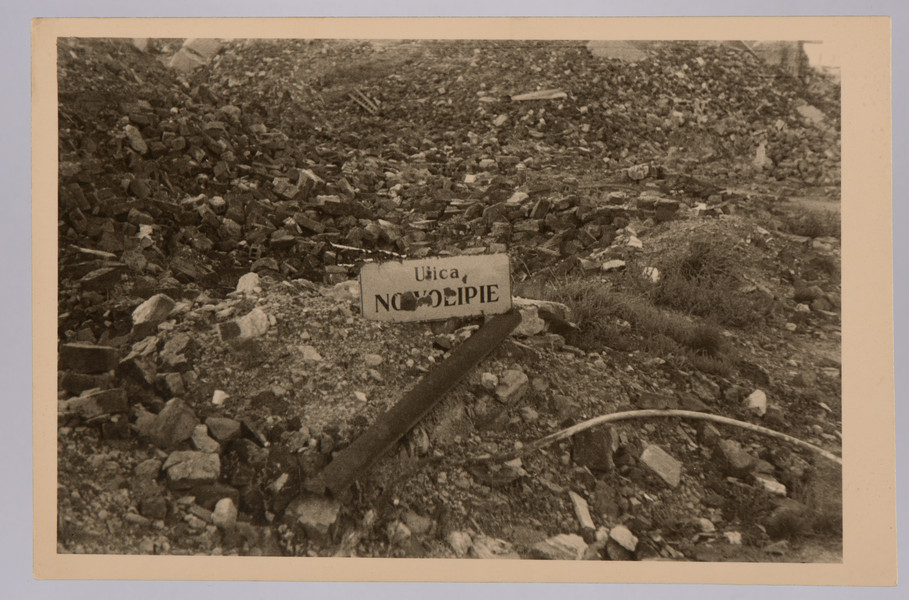

The other material include photographs taken from the “Aryan” side of the ghetto wall. They show the streets of Warsaw, the ruins and the flames over the ghetto. In one of the frames, over a dozen people climb a heap of bricks to look at the ghetto. The photos taken by Rudolf Damec were discovered in 2019 by his granddaughter Aleksandra Sobiecka. In January 2023, she brought them to POLIN Museum.